Family Office

Family Offices' Direct Investing Hunger: What's Driving It?

.jpg)

Why take the direct investing route when you have to carry out all the due diligence tasks that take time and cost money? What's driving family offices to do this and will the trend continue if the economic trends take a turn? The author of this item takes a look.

The following article is from Christian Armbruester, chief investment officer of the European firm Blu Family Office, who regularly airs views in these pages. Here he examines the popularity with family offices of direct investing. We have written about this a good deal. Armbruester brings his own specific perspective here to the topic and this publication is pleased to share these views. The usual editorial disclaimers apply to content contributed by outside writers. Readers who wish to respond should email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com or jackie.clearviewpublishing.com

Also, here is a reminder about this news service's exclusive

media partnership with Highworth, a database and

analytics firm tracking single family offices, such as those in

the Europe, the Middle East and Africa region. To

find out more, see an article here that includes a registration

link.

There are more than 10,000 family offices globally, controlling

more than $4 trillion in assets, according to a recent study by

Ernst & Young. These organisations by definition are all private,

and it is therefore not a great surprise to learn that they also

invest privately. According to another survey by UBS, 45 per cent

of family offices want to increase their direct investments in

the next 12 months. So, what is the attraction of making

investments outside of the regulated markets and, more

importantly, what are the risks? Moreover, are family offices

better equipped at making direct investments and is this trend

likely to continue?

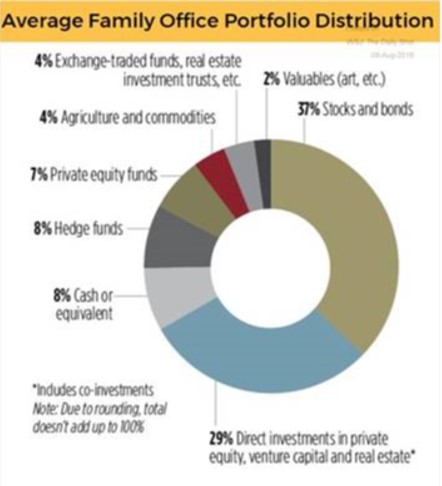

Source: UBS, Campden Wealth

To answer these questions, we must first explore the driving

force behind the need for wealthy families to set up their own

private offices or, in other words, why would anyone want to

leave the comforts of today’s private banks in the first place

anyway? Mostly that has to do with the fact that a bank or wealth

manager is an agent, who makes money from providing services,

whereas a family office makes money from principle investments.

This rather large difference in the respective risks the parties

need to take in order to succeed, has increasingly meant that

families’ purpose build their own setups to manage their wealth.

This has also made it easier to coordinate what is essentially

the main focus of a family office and the governance, succession

and behavioural risks associated with passing on wealth to the

next generation.

Clearly, there are benefits in doing things with a better focus

and perspective, but are family offices also better at making

direct investments? As ever, the answer to that question depends

on the people and capabilities that one has to perform the vital

parts of doing bespoke, private and unregulated investments. If

the family office is in the fifth generation and all the heirs

have ever done is to spend their inheritance, then you wouldn’t

think of giving junior the keys to a huge real estate development

in the middle of nowhere.

On the other hand, if the patriarch, he or she who created the

wealth in the first place is still active in the family office

and has specific expertise or a relevant skill set, then it may

make sense to run the deal in-house. That argument needs to be

taken with extreme prejudice however, and just because the family

made their money from building a great widget business, does not

necessarily qualify them to invest in a fintech or biotech

deal.

So why are families piling in? For one, there is the fear that

the markets will collapse again. Remember, families are long-term

investors and as such making an investment and not knowing

whether it will work out until far into the future is not seen as

prohibitive. Whereas, potentiality taking a 20 per cent hit on

marking equities to market is seen as a much greater risk. Bonds

are out of favour anyway, as the inflation rate for wealthy

families is running at about 7 per cent (source: Forbes Index of

Living Extremely Well), and the low (or even negative) yields

just aren’t good enough. What about hedge funds? Please, the

perception is that managers are greedy, the returns are lower

than what we can get in the markets, and there is a complete lack

of understanding of how they work or what the underlying risks

are. That pretty much leaves doing real estate, private equity or

private debt. The question is, are there ways to get exposure to

these investments without going direct? Of course, there are many

funds that provide diversified portfolios of private companies,

loans and commercial or residential property. There are also

countless structures through which one can invest to suit

individual appetites for risk, liquidity or terms.

Why invest direct versus a fund? It’s akin to buying a house that

is all done up versus a development opportunity whereby we can

add value through doing the work ourselves. Clearly, doing a

number of direct deals gives more flexibility and control over

our portfolio. We can exit deals when we want, and we can get

more bespoke exposure to specific companies, regions or sectors.

But, the amount of work remains the same and replicating the

capabilities of dedicated teams of large funds, banks or other

investment managers could be quite costly. Not only in hiring the

expertise, but also because the infrastructure and processes to

manage many projects is not easy.

It seems highly unlikely that a family office would possess all

the skill set in house to invest in a diverse portfolio of direct

deals or that they could do so more efficiently than other

dedicated professionals and the operational scale upon which they

function. It is therefore probably more of a myth that family

offices are better suited to doing direct deals, but it seems

highly unlikely that this will cause an abatement in recent

trends and we should expect family offices to do more direct

deals in times to come.