Wealth Strategies

Making History Inform Smart Financial Decisions

A world that is hungry for data and quick results often grants greater value to a popular conviction of future forecasts than to the intrinsic knowledge acquired by realized adverse events. The author of this article urges us to pay history the attention it deserves.

Events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying

economic mayhem raises a lot of questions about human behaviour.

Already, this news service has examined behavioural finance –

that framework of ideas seeking to understand why and how people

act around money in the way they do, if only to try and curb

mistakes and improve composure.

This article continues in this behavioural vein and also looks at

the case for “historical stress-testing” approaches to

investments. The analysis comes from Yannis Sardis, PhD, who is

director of Finvent

Software Solutions. (More details on Finvent below.) We

hope this article stimulates conversations, and invite readers to

email us at tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com

The usual editorial disclaimers apply to outside

contributors’ views.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it is about the

future” - Niels Bohr, Danish physicist, Nobel Laureate 1922.

Although N Bohr's quote meant to address a seminar question about

his prediction of the influence of quantum physics on the world

in the future, it sets a base for the difficulty that theoretical

and empirical sciences have in consistently relying on models of

variable complexity in order to make meaningful predictions about

future events. Our modern, information-thirsty and

quick-results-oriented, world often assigns greater value to a

popular conviction of future forecasts than to the intrinsic

knowledge acquired by realized adverse events. And there lies one

of the most common reasons of collective herding behaviour and

cognitive fallacies.

Financial decision-making is a part of a complex ecosystem that

blends behavioural psychology and investment management acumen.

Should decisions be consistently judged by the process by which

they were derived or simply by their outcome? Although the answer

relies on the definition of decision quality, it largely depends

on the compatibility between the decision maker and the judge

(who performs a second-order assessment).

In finance, a decision maker continuously faces various (known

and unknown) risks that could drastically and speedily affect the

value of a portfolio’s holdings. The day-to-day process of

evaluating the portfolio’s risk exposure to normal or Black Swan

market conditions cannot (and should not) be adequately covered

by a single risk approach and its variations (let alone by no

risk approach, as often observed in the field). Instead, a

systematic decision-making process of applying a full set of risk

methodologies should be applied to capture the adherence or the

divergence of a portfolio's probability distribution of returns

from normality.

As recent markets vividly displayed, a robust risk management

framework demands the implementation of scenario simulations

where the distribution is extremely skewed towards tail events,

situations that happen rarely. Such shocks could be caused by

various macro-economic or idiosyncratic events, which can

consequently spread widely to previously thought of as

uncorrelated choices of assets (systematic or undiversified

risk). Examples of historical crises that resulted to large

losses of invested capital within a certain period of time

(varying from days to months) include the Black Monday of 1987,

the Gulf War of 1990, the Asian Crisis of 1997, the Russia

Devaluation of 1998, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and the

(so far developing) Global COVID-19 Health Crisis.

Despite the fact that a large portion of such losses are often

due to excessive leverage, high asset valuations and

over-concentration of positions, one should seriously consider

the use of the factors underling such extreme divergences from

normality, to stress-test their often seemingly well-diversified

multi-asset investment portfolios.

We should certainly not rely on the assumption that history

repeats itself, since the background conditions, driving factors

and collective investor sentiment often differ vastly between

distant periods of economic and market activity. However, to

assess and verify that adequate capital is preserved to cover

unexpected losses, investors should attempt to estimate the

impact that the re-occurrence of such damaging historical events

could have on the portfolio performance.

This way, stress-testing would give us an idea of how stretched

the loss-tolerance levels of an investment strategy may turn out

to be during a crisis of historical precedence. To conduct such

analysis, one needs to select a historical crisis of relevance (a

subjective choice) and to apply changes to the risk factors

driving the price of various asset classes (such as equities,

bonds, credit, commodities, foreign exchange) accordingly, in

order to assess the impact to the current portfolio if an

“identical” market condition occurred. Such market shocks might

be global or local in nature, so geographical disparities in

valuation changes should be incorporated, while date ranges could

largely match those of the referenced historical event, with the

return change being the cumulative one over the entire testing

period.

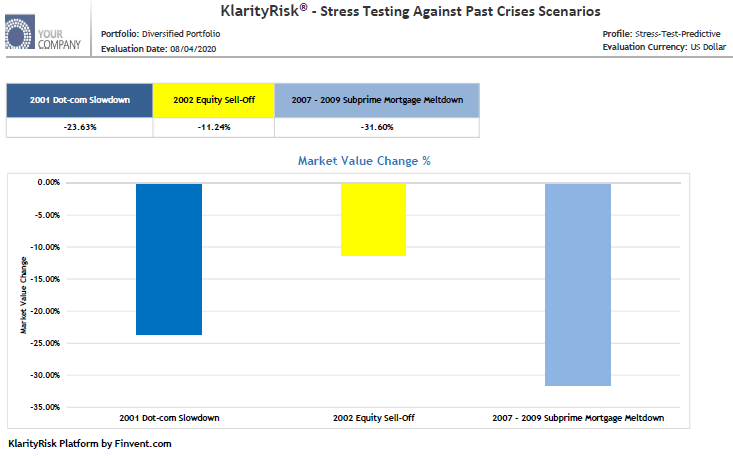

The attached graph demonstrates an example of the historical

stress-testing concept at work, for a global, multi-asset,

multi-currency diversified portfolio. The model portfolio is

heavily weighted towards US assets (with its remaining balance

allocated to Europe, UK and Japan) and it provides a multi-sector

equity exposure, whilst its fixed income component includes both

corporate credit and sovereign bond holdings. The user-selected

historical crises are the 2001 dotcom bust, the 2002 equity

sell-off and the 2007-2009 subprime mortgage meltdown periods,

for which the simulation analysis depicts the market value

changes of the portfolio should the market conditions which

characterized these past crises occurred again.

To adjust historical scenarios to modern frameworks, a risk management process should offer the functionality for stress modelling based on a combination of extreme past crises and the customization of factors to the current correlation dislocations, since each investment strategy may be subject to different set of risk factors. Value-at-Risk-based methods provide a decomposition of risk exposure into its core sources, thus identifying over-concentration or risk-adjusted under-performance pockets.

As the above graph illustrates, risk measurement cannot be put on ice until market conditions dictate its sudden use. Extreme market events are evidently more frequent and violent than commonly thought of and their effect on portfolio performance should be diligently and continuously assessed. The ability to implement a multi-faceted portfolio risk analysis will enhance a manager’s confidence to the capital adequacy a strategy or a firm needs to retain in order to cover significant losses in utmost detrimental market conditions.

About Finvent

FINVENT Software Solutions is a trusted provider of financial

software applications and custom engineering services. The

award-winning KlarityRisk platform specializes in investment risk

analytics and fixed income performance attribution reporting,

offered to financial institutions in European and African

countries. Finvent is the sole SS&C Advent distributor

worldwide and its products are natively integrated with those of

SS&C Advent, and a Partner of FactSet.