Technology

GUEST ARTICLE: Making Money From The High Frontier - Investment And Space

Space flight and development is becoming an increasingly important investment field. This article, from a wealth management business, examines some of the trends.

Anyone scanning the news lately will, amid the geopolitical gloom, have noted a buzz around private-sector space flight and innovation. This represents something of a shift from the days when space flight was done almost entirely by government agencies such as NASA and its French, Russian and Chinese counterparts. Like it or not, the state is likely to remain a major player in such activity for military and other reasons, and for the foreseeable future. But the commercial side of “space faring” has been a talking point for some time. It appears to be gathering pace. So, what should investors and advisors conclude? This article, by Shilen Shah, a bond strategist for Investec Wealth & Investec, examines the market. The editors of this publication are delighted to share these insights on this topic. We invite readers to respond with their views.

For many investors, space remains a moonshot – i.e. a potentially

ground-breaking but highly speculative investment. The

commercialisation of space, however, can be traced back to the

origins of the original Moonshot (the Apollo project) and the

competition between the US and USSR. After Sputnik was launched

by the Soviets in 1957, the US government launched a massive

investment programme which, in competition from the USSR,

eventually started the space race.

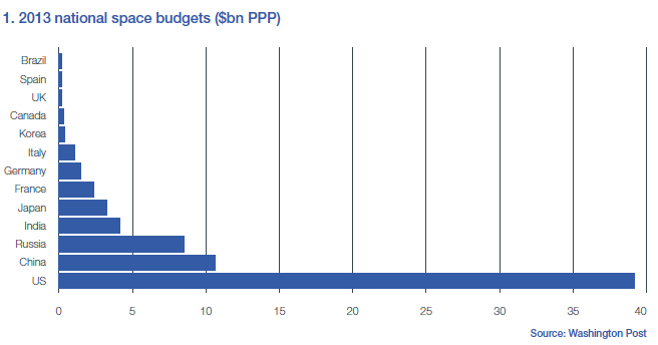

However, since the end of the Cold War, and amid financial

constraints, the US and USSR/Russian governments’ commitment to

space has waned somewhat. A number of other countries – notably

China, India and some in Europe – have developed significant

civil space programmes, although they are dwarfed by that of the

US (see chart 1 below).

Even with the spending power of the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration (NASA) the US is still reliant on other

nations, having recently signed a contract with the Russian

Federal Space Agency for the transportation of US astronauts to

the International Space Station (ISS) via the Soyuz spacecraft.

On a per-seat basis, NASA is estimated to be paying the Russian

government around $81 million for each astronaut it sends to the

ISS.

NASA’s main focus is on its hugely ambitious Space Launch System

(SLS), a long-term programme to produce a rocket system that will

penetrate further into the solar system via the Orion spacecraft.

In view of this priority, and to address the reliance on the

Russian Federal Space Agency for sending astronauts to the ISS,

the US government has started to look to the development of

private sector alternatives, with companies such as SpaceX and

Boeing actively developing new launch systems.

In Europe, the key player in the rocket sector remains Ariane,

which is owned by a consortium of European aeronautical

companies. It was established in 1980 and has a long track record

in the satellite launch business. Today it faces significant

competition from SpaceX – the private space company formed in

2002 by Elon Musk.

As with Musk’s NASDAQ-listed Tesla Motors, the electric car

manufacturer, SpaceX is positioned as a disruptive business with

Musk aiming to alter the market significantly. Although the

Ariane V rocket system has a significantly higher payload

capacity than SpaceX’s Falcon, the latter is significantly

cheaper per kilo (see chart 2). SpaceX is also looking at the

potential to re-use Falcon 9 rockets, which would bring the cost

per launch down from tens of millions of dollars to $5 million-$7

million.

The group is also developing a Falcon Heavy rocket system, with a scheduled first launch in 2016. At launch it will be the most powerful rocket system since Apollo, with a significant lower cost per kilo of payload.

Satellites

Another feature of the commercial use of space is satellites.

Historically, the costs associated with developing satellites

have been high because of the use of bespoke parts; however

advances in smartphone technology have also disrupted the

satellite development and launch model. One significant area of

innovation is the commercialisation of Cubesat – a 10cm cubed

satellite weighing no more than 1.33kg.

Cubesats were initially developed as a low cost scientific

research tool but in view of their flexibility (e.g. multiple

cubesats can be placed in space via a single rocket launch) the

commercial sector is now looking at their potential use. Cubesats

are currently at the commercial infancy stage, but forecasts

suggest around 1,000 nanosatellites (weighing 1-10kg) will be

launched in the next five years.

One company that has been leading the development of

nanosatellites is Surrey Satellite Technology (SST), initially a

spin-out of the University of Surrey’s aerospace department and

now majority owned by Airbus (AIR). The group has a dominant

position in the small satellite sector (3.5kg-600kg) with a 40

per cent share of the global market. In contrast to larger,

expensive satellites, nanosatellites can have specific uses with

their limited lens resolution making them a cost effective

solution for applications such as crop and geographic

monitoring.

Another area in which SST is making inroads is the development of

geostationary satellites for Eutelsat (a French competitor to

Inmarsat) that are ideal for voice and data communication.

The company is also building equipment for the Galileo Project (the EU’s alternative to the US Global Positioning System). Leftfield developments in the sector include Facebook recently signing an agreement with Eutelsat to launch a satellite in 2016 to provide internet access to remote communities in 14 Sub-Saharan African countries. Other players in the UK satellite sector include AIM-listed Avanti Communications (AVN), which focuses on providing communication services to a number of telecom companies on a global basis.

Future endeavours, political and practical

issues

Although space has been accessible for more than 50 years, space

tourism is at the limits of practicality, with many looking at

the sector with a degree of scepticism. However, from a broader

perspective, the combination of lower-cost rocket launches and

cheaper satellites suggests space has entered the commercial

mainstream.

As with other new sectors, risk factors around space are ever

present. One key factor is regulation, with governments licensing

individual rocket launch systems. In contrast to earth-based

regulation, space itself remains an unregulated area with no

sovereign state or corporation able to "own" any part of it.

From a practical perspective, issues such as space debris will

become a growing concern, especially if the number of vehicles

orbiting the earth increases in the near future. Practical steps

such as minimising space junk and the manoeuvring of defunct

satellites so that they can be burned harmlessly in the

atmosphere still require the co-ordination and agreement of

commercial and government operators.

Notwithstanding the challenges, after a period that saw the Space

Shuttle programme decommissioned and government interest in space

waning, the private sector has picked up the baton and is running

with it.