Banking Crisis

GUEST OPINION: Getting Blood From A Stone: Research Affiliates On Greece's Debt Agony

The research organisation examines what is at stake as Greece enters the possible endgame of its traumatic membership of the eurozone.

Events are moving so fast that by the time these words are

published there may have been a resolution of the Greek debt

crisis which could either result in the country remaining in the

eurozone or leaving it, probably to return to its old drachma

currency. According to various reports yesterday, a new Greek

offer for a cash-for-reforms deal has fuelled optimism that an

agreement could be reached; prospects for a deal sent Greek

equities soaring by almost 7 per cent yesterday at one

point.

A great deal of ink has been spilt on the subject; this

publication is running detailed commentary from Chris

Brightman and Shane Shepherd of Research

Affiliates. We urge readers to respond with their views and

they can contact the editor at tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

The old saying “you can’t squeeze blood from a stone”

vividly describes the futility of trying to extract more

resources from something than it has to give. The expectations

the Greeks have for renegotiating their debts requires them to do

exactly this, squeeze blood from a stone. Only by increasing tax

collections can Greece reverse the painful reduction in

government spending, services, and employment known as

austerity.

Today’s Greek crisis is no longer about its involvement in the

euro. Nor is it about the disconnect between unified monetary

policy and disparate fiscal policies - as important as that

inconsistency is. The present standoff is a powerful

demonstration of the limit to debt-financed consumption.

The amount of debt that Greece has accumulated is staggering.

Where will the money come from to repay the mountain of

obligations as they come due? In principle, Greece can take one

of three routes:

1. Create the necessary new wealth through economic

growth;

2. Transfer resources from existing programmes to debt service,

or

3. Kick the can further down the road.

But, given its meagre growth prospects, the Greek economy cannot

hope to generate the new wealth necessary to repay its maturing

debts. And with the recent election of the Syriza party, voters

have effectively rejected the implausibly deep and sustained cuts

in government spending and services necessary to meet principal

and interest payments. Greece may be able to “extend and

pretend”- stretch out its past debt and make believe it will be

able to pay it off - but no new credit will be available. The now

unavoidable and obvious result is that Greece has hit its limit

for debt-financed consumption.

The troika of European lenders (the European Union, the

International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank) who

hold Greece’s fate in their hands are insisting that the

Greeks cut government spending in order to “live within their

means”. But the reforms demanded go far beyond shifting amounts

between lines in the budget. Implementing the reforms stipulated

by the troika requires a dramatic shift in the entire ethos that

characterises the country’s economic culture.

For Greek citizens, tax evasion rises to the level of a national

sport. The Wall Street Journal recently estimated that

at the end of 2014 the Greeks owed their government €76 billion

($86 billion) in unpaid back taxes, roughly 35 per cent of GDP!

The Syriza party ran not only on an anti-austerity platform, but

also with strong anti-tax rhetoric. As the party’s election

became more and more likely, many Greeks halted tax payments,

resulting in January 2015 tax revenues that were 23 per cent

below expected levels (Karnitschnig and Stamouli, 2015). Needless

to say, this does not herald fundamental change.

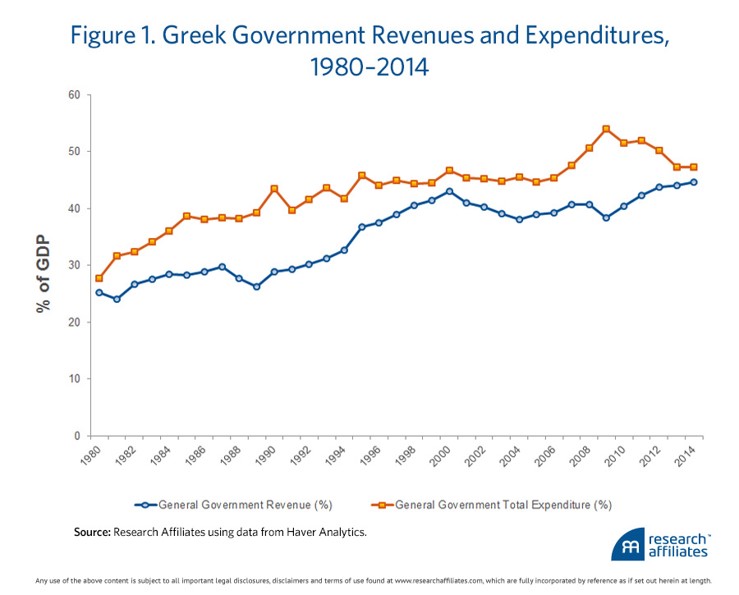

Spending norms also require radical adjustment. As figure

one shows, Greek government expenditures have consistently

and dramatically outpaced revenues over the last 35 years!

Figure 1

Obviously, this phenomenon was not brought about by Greece’s

entry into the eurozone in 2001, although the fiscal deficit did

reach a peak gap in 2009, with general government expenditures

climbing to 54 per cent of GDP and government revenues to 38 per

cent.

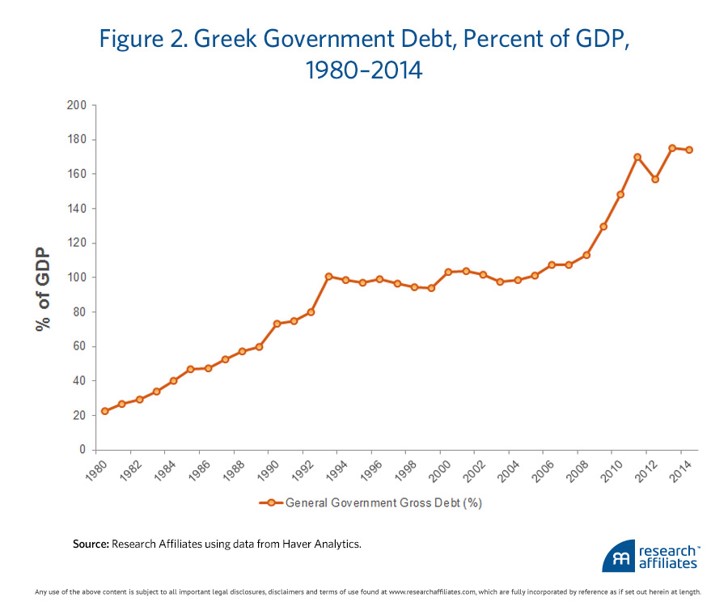

Many decades of unchecked spending and lacklustre tax

collections, as shown in figure two, have resulted in government

debt levels soaring to 175 per cent of GDP, a ratio that has only

risen more with the recent programme of fiscal austerity.

Figure 2

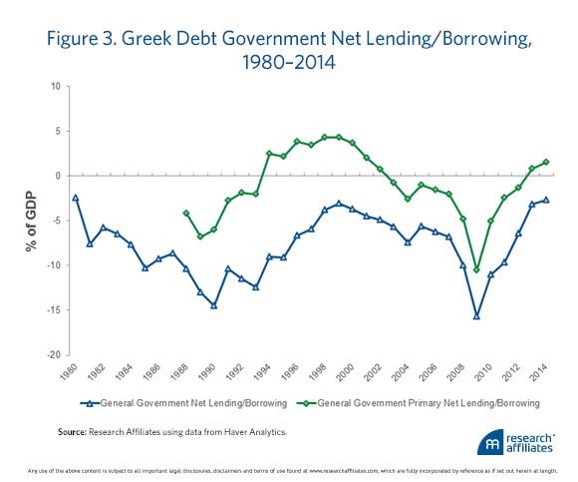

True, spending restraints have helped push Greece into a primary

budget surplus, illustrated in figure three, for the first time

since the dubious statistics of the mid-1990s and very early

2000s were published. (The data were probably manipulated as

Greece pushed for admittance to the eurozone.) But even if debt

levels have fallen, GDP has fallen faster - at an average rate of

about 6 per cent per year over the last five years. The

prescribed cure has arguably made the patient sicker.

Figure 3

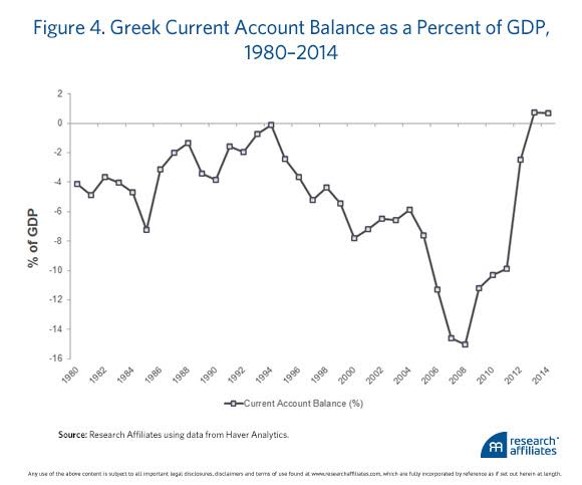

A simple calculation on a bar room napkin defines the scope of the problem. With the current account positive for the first time in more than 35 years, as figure four shows, let’s assume a relatively rosy scenario: Greece sustains the 3 per cent primary budget surplus demanded by the troika. In addition, the government brings the real GDP growth rate to a level equivalent to the real interest rate on its debt through a combination of current account surpluses and slower cuts in government spending. This is not an easy task. If, however, this scenario plays out, it would still take 30 years to bring Greece’s debt levels down to a more reasonable - and perhaps still unsustainable – 85 per cent of GDP. This is a big ask for a country that voted for political upheaval following just three years of austerity policies.

Figure 4

And so we arrive at the present impasse. Greece cannot borrow

more. By definition, the pool of lenders is exhausted once the

lender of last resort walks away.

Regardless of whether Greece’s participation in the euro

facilitated its final burst of borrowing, exiting the euro now is

no panacea. Suppose the Greeks were to depart from the eurozone,

repudiate their debts, and return to the drachma. Greek banks

would fail, and capital controls would be imposed. Devaluation

would increase export competitiveness but cause imports to become

prohibitively expensive.

With complete control over both fiscal and monetary policy, the

Greek government would be free to print and spend drachmas

without restraint. But those drachmas would not buy many goods

and services priced in euros or dollars unless, and until, the

government’s spending was limited to its tax collections. In

this scenario, the Greeks would still be constrained to living

within the resources generated by their real economy.

So, the spotlight on the Greek drama the world is watching

illuminates the danger that other countries with growing external

debt should keep top of mind: high debt burdens, above and beyond

those that can reasonably be repaid by future real economic

activity, will invariably bring about inflation or default. If

debts cannot be repaid, they will be—in countries where they can

be - simply inflated away. But we all know, of course, that

inflation is just a gradual default.

The choice between inflation and default is essentially based on

social and political choices (Rogoff, 2014); the level of

inflation a nation accepts corresponds directly to its

preferences about spending, taxation, transfer payments, and the

like. This is the stuff of bloodless stones and Greek

tragedies.

Endnotes

1. Because bar room math does not allow for compounding,

debt-to-GDP ratios should decline slightly faster than estimated

here. Also note that inflation in the euro may (if not

incorporated into the interest rate Greece pays) help reduce the

debt-to-GDP ratio, just as the current deflationary trends in the

euro are exacerbating them.

2. Cochrane (2011) provides a short review of the implications of

such a scenario.

References

Cochrane, John. 2011. “The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level and

Its Implications for Current Policy in the United States and

Europe.” Presentation at the Fiscal Policy under Fiscal Imbalance

conference hosted by the Becker-Friedman Institute and Federal

Reserve Bank of Chicago (November 19).

Karnitschnig, Matthew, and Nektaria Stamouli. 2015. “Greece

Struggles to Get Citizens to Pay Their Taxes.” The Wall Street

Journal (February 25).

Rogoff, Kenneth. 2014. “The Exaggerated Death of Inflation.”

Project Syndicate (September 2).