Alt Investments

Some Private Equity Valuations "Incredibly Inflated", But Sector Has Legs - Conference

Industry figures said there are "red flags" around valuations in today's private equity market space, a sector that has drawn in heavy inflows from wealth managers recently.

Some private equity valuations are “incredibly inflated” and the

asset class is not immune to shifts in the economic cycle, but

structurally the sector is here to stay and an important

destination, attendees at an investment forum heard.

“There will be a cyclical, not structural, adjustment,” Jean Eric

Salata, chief executive, founding partner at Barings

Private Equity Asia, told the Wharton Global Forum in London

late last week.

With more than $1.0 trillion of unused capital, aka “dry powder”

in private equity alone, this publication has regularly been told

that some investors fret that yields will be squeezed. A few days

ago, Luca Paolini, chief strategist at Pictet Asset

Management, told this news service that private equity was

highly cyclical as an asset class with, in his view, few

diversification benefits at present.

Private equity has drawn in investments over recent years because

it pays higher returns than for conventional listed equities –

but the drawback is far lower liquidity. Private equity

investments are typically held in for about five years or so.

There has been some improvement as a secondary private equity

market has developed. According to figures quoted at the Wharton

forum, the assets of “secondaries” now stand at around $180

billion globally.

The median private equity deal was 12.9 times a measure of

company earnings, beating the previous record of 10 times

earnings in 2006, according to Murray Devine Valuation Advisors,

a firm based in Philadelphia, last year (source:

Institutional Investor, April 2018).

It appears that those involved in the asset class aren’t getting

unduly worried: Preqin,

the research firm tracking the sector, has reported that nine out

of 10 investors it has polled are satisfied with the performance

of the asset class, and 31 per cent intend to invest more in

private equity this year than they did a year before.

“You have to accept that this [private equity] is a long-term

asset class that will have cycles along the way. At the moment

valuations are incredibly inflated and this is a bit of a red

flag alert environment,” Salata said. He was speaking alongside

Kurt Bjorkland, co-managing director, Permira Holdings,

and Afsane Jetha, managing partner and CEO, of Alta Semper

Capital.

Benefits of being locked up

Salata said there are some benefits to the lock-ups involved with

private equity – an investor has some freedom to wait in a

falling market to buy assets at cheap valuations and profit from

subsequent gains. “That is what appeals to people about the asset

class,” he said.

Private equity is often measured by the “vintage” of a fund (like

wine, the starting point is from when the fruit is picked) and

practitioners suggest investors hold a blend of vintages so that

funds coming towards the end of their “normal” investment life

sit alongside younger ones.

A figure mentioned by panellists was how there are $500 billion

or more of private equity investments in funds created before

2008 – the year of the financial crisis.

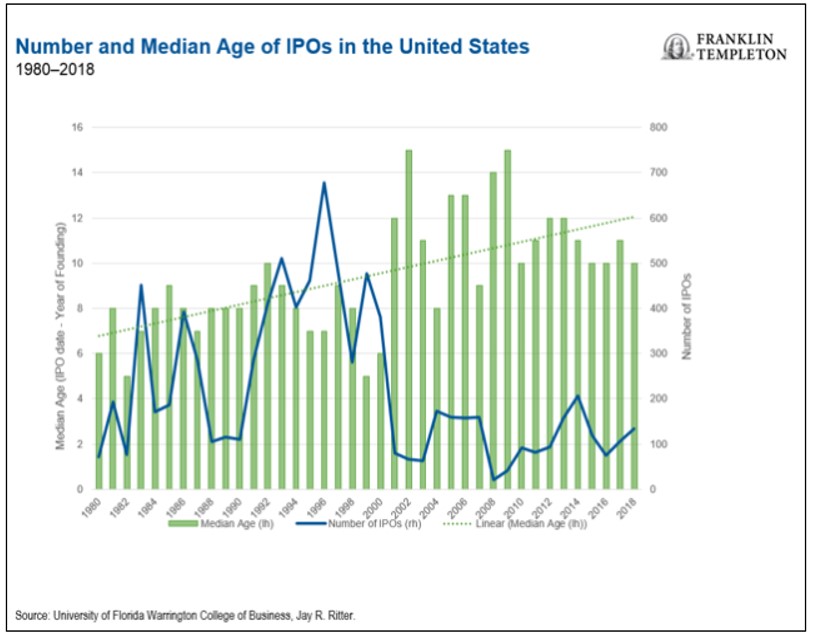

Permira’s Bjorkland argued that evidence suggests privately-held

firms (rather than those listed on public markets) tend to be

more robust financially and that a lot of young entrepreneurs

today don’t think the ideal end-point is an initial public

offering, as might have been the case more than a decade ago.

Data suggests that firms are staying “private for longer” than

was the case, say, during the 1990s dotcom boom. On the other

hand, the development of a secondaries PE market suggests that

investors seek exits if the older route of selling shares becomes

less available.