Investment Strategies

Brexit's Impact On The EU - A View From RBC Wealth Management

The wealth management firm examines the UK's fractious relationship with the EU bloc and what the effect Brexit may have on the remaining members of the Union.

Written by Frédérique Carrier, head of investment strategy, RBC Wealth Management, this overview analyses how the UK's departure from the European Union will affect the bloc. The item was originally issued as a report by the bank and is republished by this news service with RBC's permission. As ever, the usual editorial disclaimers apply; readers who want to respond can email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com

Dawn is breaking for a new Europe, with changes that will test

its resolve. We look at what awaits the EU and what it holds for

investment strategy.

The departure of the influential UK from the EU is the first

setback for the bloc’s integration experiment. But paradoxically,

it seems to have rallied support for the EU within the remaining

27 countries.

The loss of the UK’s contribution to the EU economy and its

budget is unfortunate but should be manageable.

Calls for a larger role for fiscal policy continue. Fiscal

rectitude remains the order of the day but increasingly appears

to be an antiquated model. Change may be afoot.

The departure of the UK from the EU will be felt in the bloc, but

this episode has also increased the union’s resolve and we expect

it to adapt to the new state of affairs. After a weak 2019, the

EU appeared to be turning the corner as 2020 began, but the

manufacturing shutdowns in China brought on by the coronavirus

outbreak are likely to push any European recovery into the second

half of the year. Some anticipated fiscal stimulus should help

matters on the continent, and we continue to see selective

opportunities for investors.

The first setback

The EU began in 1951 as a coal and steel trading bloc comprising

Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West

Germany. Initially, the main purpose was for West Germany to

expiate its role in World War II. By partly giving up its

national sovereignty and integrating into a larger, demilitarised

trading group with strict procedures, West Germany hoped for

rehabilitation.

The other five founding members saw an opportunity for

reconciliation and sought security in numbers, while France also

viewed the group as a potential counterweight to UK and US

influence. Since its formation, the bloc has ushered in a period

of peace and prosperity unseen in the continent’s history.

The UK was the first member to depart the group, which had grown

to 28 nations. Despite being a late joiner in 1973, the UK became

an influential EU member, given the size of its economy (second

only to Germany) and penchant for free market practices. Along

with the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Ireland, it

formed a group known as the Nordic Alliance, which offset French

policies favouring state intervention. The Netherlands, which has

tended to keep a low profile despite being the EU’s fifth-largest

economy, is likely to fill the vacuum left by the UK, though the

Nordic Alliance may see its influence wane minus the UK.

However, the UK’s departure seems to have rallied support for the

EU within the remaining countries as the political chaos that has

engulfed the UK since the June 2016 Brexit referendum has not

gone unnoticed.

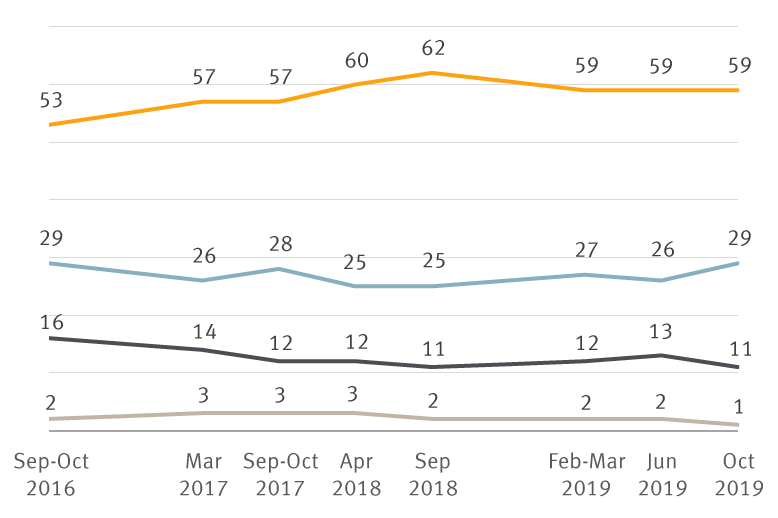

Support for the EU within member states has increased

since the Brexit vote

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Parlemeter 2019 (92.2), QB12

In fact, many anti-establishment populist parties across EU

countries have mellowed their EU scepticism, instead railing

against immigration to win votes. Populist parties in Italy,

Austria, and Hungary all suffered electoral setbacks in 2019 -

though admittedly their poor showings could reverse if

immigration concerns return to the limelight. As a sign, the

danger of a populist government in Italy seems to have passed,

the spread of Italian government bond yields over German Bund

yields has recently fallen from a peak of 324 basis points (bps)

back to the March 2018 level of just 135 bps.

Modest economic consequences

Now with 27 members, the EU will remain one of the top three

economies in the world, though its share of global nominal GDP

will fall from 16 per cent to 14 per cent, according to the

International Monetary Fund.

Should the EU lose complete access to the UK market due to the

breakdown of negotiations over a new trade agreement, we believe

the impact would be modest as EU exports to the UK represent only

three percent of EU GDP. Moreover, the damage would be partially

offset by some diversion of trade, investment, and skilled

migrants away from the UK to the EU.

Similarly, the fiscal consequences of losing the UK’s

contribution to the EU budget should not be exaggerated. First,

the EU budget is a mere 1 per cent of the total value of the EU

economy - versus the US federal budget at some 20 per cent of GDP

and UK government spending of close to 40 per cent of GDP - as

most of the fiscal spending in the EU is done by national

governments.

Second, the loss of the UK’s net contribution to the EU budget,

which amounted to some £9 billion ($11.5 billion) in 2018, will

be felt in Brussels, but only over time. The UK will honour its

legacy financial obligations of more than £30 billion ($43

billion) per the terms of the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement.

Yet negotiations for the EU’s next seven budget years (2021–2027)

are particularly tricky given Britain’s departure, as EU members

have to agree how to split the bill.

Challenges for the short term

For now, the EU faces other challenges. After a difficult 2019,

economic activity at the start of 2020 had pointed to a healthy

pickup in growth, but this improvement is now being threatened by

the coronavirus outbreak. Factory shutdowns in China are

affecting not only the EU’s export demand but also some of the

supply chains of European companies. Eric Lascelles, chief

economist for RBC Global Asset Management Inc, estimates that the

outbreak may reduce EU economic activity by some 0.2 per cent,

though the magnitude of the impact is likely to depend on the

duration and severity of the shutdowns. RBC Capital Markets

expects 2020 GDP growth of 1 per cent.

Calls on national governments for more fiscal stimulus are coming

from many quarters, including the European Central Bank president

Christine Lagarde, who is aware that there are limited monetary

policy manoeuvres available with interest rates already in

negative territory. Moreover, the region has considerable spare

fiscal capacity, and with borrowing costs low, fiscal stimulus

would not only be appropriate but also affordable. Indeed,

France, Italy, and the Netherlands have already dipped into

government coffers a little in 2019, the former to appease the

Yellow Vest protests against fuel tax hikes.

However, Germany is resisting these calls so far. Its

constitution bans structural deficits of more than 0.35 percent

of GDP. As a result, Germany has run a fiscal surplus since 2014,

which peaked at 1.9 percent of GDP in 2018. German officials say

they will do away with that constitutional rule if conditions

warrant it. But with the economy at full employment, Chancellor

Angela Merkel’s government feels that the current slowdown isn’t

sharp enough yet to justify a major one-off fiscal boost.

But it can devise strategies to work around, such as off-balance

sheet vehicles issued by public bodies which can tap financial

markets without appearing on the central government’s books.

Recent incentives to speed up the conversion to cleaner energy

were partially financed in this manner and could soften the

impact of the slowdown.

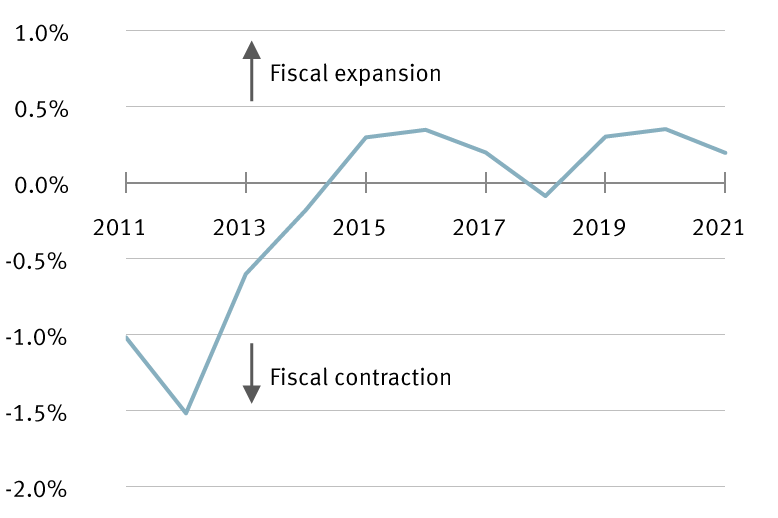

A bit more spending expected in 2020

Fiscal spending could be more generous but it would require

changing the fiscal framework.

Source - RBC Capital Markets; excludes interest payments

For now, RBC Capital Markets expects fiscal stimulus of 0.4 percent of GDP for the EU as a whole in 2020.

Lagarde is also trying to push the EU Commission, the executive

branch of the EU, for changes to fiscal policy. The commission

wants to loosen the current EU fiscal framework, which targets a

debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent and a deficit of no more than 3

per cent of GDP. These simple rules seem dated and too

restrictive for a time of record-low borrowing rates and meagre

growth. The EU Commission intends to propose changes by the year

end.

Investment strategy

Now a bloc of 27 members, we believe the EU will evolve, guided

by its culture of consensus which was able to produce the desired

outcome in the divorce negotiations with the UK. With resilient

domestic demand underpinned by some fiscal support, we would

expect the eurozone’s economy to eke out enough growth to

generate mid-to-high single-digit corporate earnings growth.

With the STOXX Europe 600 ex UK Index’s undemanding

price-to-earnings valuation of 14.3x based on 2021 consensus

estimates and a dividend yield above 3 per cent, there is room in

portfolios for an allocation to well-managed European companies

with strong business models and leading market positions, in our

view. For example, we believe investors can find opportunities in

the consumer spaces or the Industrials sector from companies

positioned to benefit from structural trends, such as increased

infrastructure spending, urbanisation, and digitalisation.