Philanthropy

Younger Philanthropists Press Accelerator

Where are the fault lines growing between traditional philanthropy and direct giving? What do younger generations want from investing that financial institutions aren’t perhaps delivering? And how is ESG hindering more than helping investors tackle climate change? We take a look.

Philanthropy has been caught up like everything else this year in a pandemic that has outwitted just about everyone. The health crisis has raised shaming inequality and climate crises that markets and governments have been painfully slow to address.

Enter the ordinary individual you might say to hurry progress along.

Just as crowd sourcing has found its place as a direct and easy way to invest in companies and ideas, especially for younger investors, so are some corners of philanthropy seeing fresh momentum.

The Global Returns Project, a new effort led by ex-City fund manager Yan Swiderski, aims to raise $10 billion annually by encouraging individuals to commit 0.25 per cent of their savings and investments annually to non-profit climate solutions. Capital raised will support five pre-screened charities which are tackling the climate crisis most effectively.

Swiderski is going after the private individuals who PwC has identified as owning roughly $140 trillion of assets globally - split roughly evenly between mass-affluent holding $100,000 to $1 million and high-net worths and above.

Some are already well-served by wealth managers and philanthropy departments, but many are not, Swiderski argues, but are still asking, ‘What can I do to help reverse climate damage, and please make the approach simple and direct…'

“Our thoughts were, all these people are saving money for the future and making investment decisions that impact the real world, and many are becoming concerned about the climate crisis. If we can get some tiny portion of that money every year to put towards climate solutions, we could mobilise a huge amount of effective capital,” Swiderski said, making his case on a recent call as part of our seasonal look at giving in an extraordinarily tough year.

And it has been especially tough on charities. While the public has been generous, donating an extra £800 million this year, income from fundraising events has been crippled. As an example, even though this year’s London Marathon took place, with entrants running their own solo marathons in October, the windfall captured only around a quarter of the £66 million the event raised in 2019 when everyone was running together. Charities, like people, thrive on mass spectacle, which we have been robbed of this year.

The US paints a similar picture. Figures from the Gates Foundation show that household giving and volunteering was up by more than 10 per cent for the year in response to the pandemic, but usual fundraising has collapsed.

Swiderski’s fledgling project materialised from years working as a fund manager and recognising that markets can’t solve everything, and certainly not at the pace needed now to tackle the climate emergency.

“Trustees may be constrained by fiduciary obligations and other investment restrictions but private individuals are not,” he said.

The group screened around 120 charities before settling on five to support initially. It scored each on their ability to draw down C02 and for their work in three climate areas: natural carbon solutions (protecting forests, planting trees, reducing pressures of deforestation); renewables (delivering clean energy to around a billion people who have no access to power at all); and advocacy (promoting good policy and enforcing existing environmental laws).

Investing “for good” has become a confusing minefield begging for some clarity. The industry has been flooded this year with ESG and green finance solutions that have bewildered investors and created enough room for greenwashing to drive a bus through.

So why wouldn’t a quality-assured tick-box approach to “re-investing in Earth,” as Swiderski likes to refer to his business aims, appeal to overloaded investors?

The group has taken its campaign directly to the public on a lofty journey of raising £10 billion annually but it also needs endorsement from financial institutions.

“If the message of what you need to do is coming from your IFA, your private bank, or wealth manager, it immediately normalises it,” Swiderski said.

“What we are doing is very much complementary to an ESG strategy but we also need to think about the banks we use," he said. "The big polluters, the fossil fuel companies and utilities, are debt financed, so it is banks and bond markets funding them, not share markets. If I sell my shares in Shell, which I did some time ago, that doesn’t affect Shell’s life. But if no-one lends money to Shell that really does change things,” he said.

In pre-launch pitches to fund and asset managers, comments ranged from "this is too hard to pass at board level", to "this is too costly to implement", to "is this something a client even wants?" Swiderski said, noting pushback in some wealth management circles. Others, he said, have since been back in touch expressing interest, though when pressed, he said it was too early to be naming them.

Whether the sector thinks it has climate change covered, through co-investing philanthropy projects or private capital pouring in at the direct company level, Swiderski argues that these are for-profit initiatives that may take years if not decades to roll out.

No time to waste

And we don’t have that luxury of time.

“There is no market solution for protecting rainforests. There is no fund you can invest in for suing coal fired power stations in Europe or advising the Chinese government on good environmental policy, which is the sort of work Client Earth is doing,” he says, in reference to one of the project’s chosen launch charities.

ClientEarth famously took the UK government to court over breaching its own air pollution rules, and won.

As for philanthropy departments, “they don't exist for those using an online brokerage at Fidelity or Schwab." Another problem of philanthropy in its present form is its randomness, he argues.

“People don’t think about giving in proportion to their wealth. They think about the nominal amount, and with a few notable exceptions, data suggests that as people get richer they give away smaller and smaller proportions of their wealth." The fact that by some estimates only around 3 per cent of total giving is currently going into environmental projects is not helping.

“If we don’t get on top of biodiversity and climate, so many of the other problems that philanthropy seeks to address are going to get many times worse,” Swiderski said.

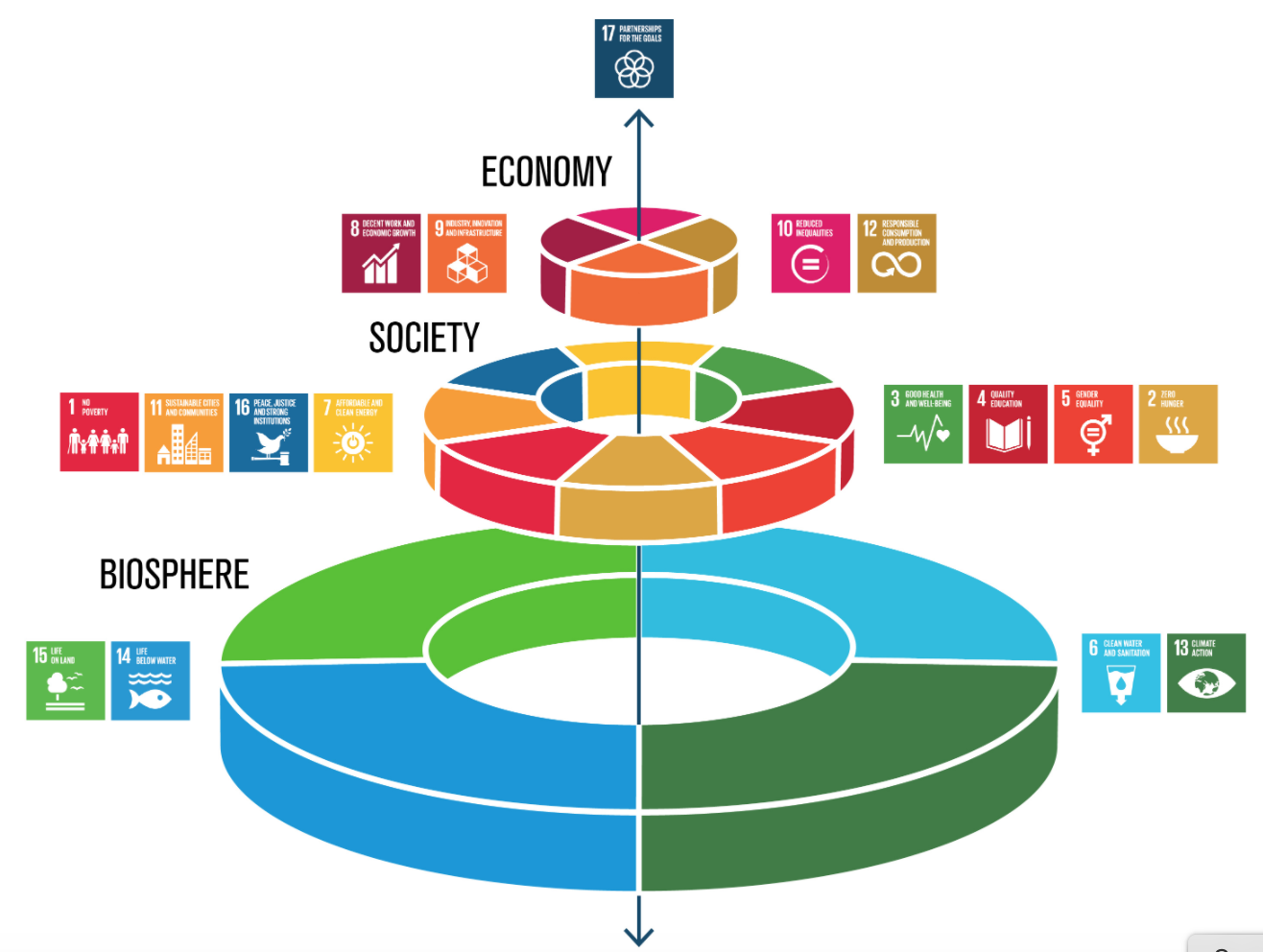

His response raises legitimate questions about how faithfully green finance has wrapped itself around the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals and whether efforts should be focused on just a handful rather than giving investors a smorgasbord to choose from that may dilute impact.

The Stockholm Resilience Center, a research arm of Stockholm University, has argued for this approach. (The schematic below shows how its chief scientists have re-worked the UN’s planetary goals to revolve mostly around food and in a different hierarchy).

“The four fundamental [SDGs] are clean water, life below water, life on land, and climate action,” Swiderski says. “If you don’t have those all the others are irrelevant because they all depend on those four.”

The Global Returns Project has signed up 100 participants in a pilot that is already moving capital into the partner charities.Those giving can put donations they've already made to climate charities towards their annual 0.25 per cent commitment, with 100 per cent of it going to their selected charities.

The names of the launch charities largely speak for themselves:

The Trillion Trees initiative; Rainforest Trust UK; Ashden, which

supports sustainable energy enterprises globally; Global Canopy;

and ClientEarth.

Millennials

Where Swiderski hopes to find support is among Millennials. This

change-making generation controls around $24 trillion of assets

and most want to invest sustainably but might not be looking at

traditional markets for answers.

“There is a tremendous amount of inertia in the fund management business. A lot of existing models are very profitable just as they are. So why do I need to change anything?" Swiderski said.

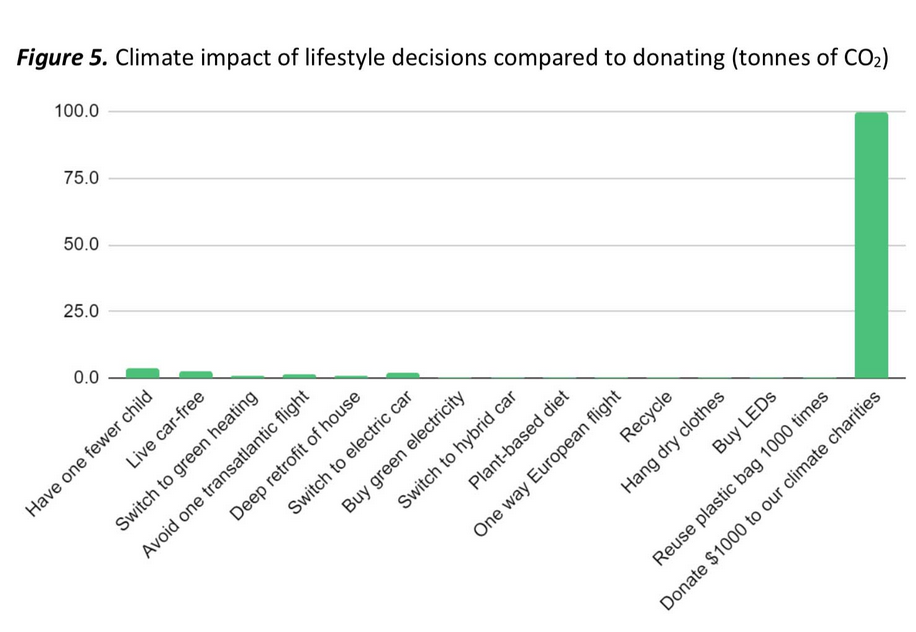

This reappraisal of giving among younger professionals is reflected in organisations such as the UK charity Founders Pledge. The charity was spun out of a network of entrepreneurs, many of them technologists, who wanted to put their wealth to the best possible good while also creating a likeminded space to share progress. The group is known for publishing analytical reports on climate and lifestyle decisions and their impact on carbon emissions.

It has calculated that a typical person emits five to 20 tonnes of CO2 annually, and that giving to the most effective climate charities can abate a tonne of CO2 for the equivalent of a $10 annual pledge. It also examines the various trade-offs and unintended consequences of our lifestyle decisions, from choosing to eat chicken over beef to the effects of driving an electric vehicle in one economy over another. There are many artful nuances. It is especially attentive on the subject of “offsetting.”

The two climate charities the group recommends to a mainly

entrepreneurial member base are the Clean Air Task Force and the

Coalition for Rainforest Nations, with each running annual

budgets of less than $8 million per year. “For this relatively

small amount, they have each played a leading role in political

campaigns which have had a huge effect on global climate policy,”

Founders Pledge said. (See some of its research outlined in the

chart below.)

Widening appeal

John William Olsen, who manages impact strategy for M&G noted that impact

investing is no longer the preserve of institutional and high net

worth investors. “The emergence of listed impact equity funds has

significantly opened up the space to members of the public who

want to make a difference with their money.”

Another growth driver “has been the simple fact that impact strategies are more tangible and easier to understand than environmental, social and governance investing,” Olsen said, pointing to ESG’s dismal measurability record.

Louis Larere, sustainable fund manager with Oyster is another bemoaning the limitations of ESG ratings and taking a purely quantitative approach to responsible investing.

“As we await the EU Taxonomy Regulation’s clear framework for labelling sustainable financial products, due to become law by the end of 2020, we believe investors should be aware of the limitations of ratings and heed the wisdom behind avoiding overvalued ‘green’ stocks,” he said. As they stand, he continued, “ESG factors do not help form an opinion of an industry’s impact on the world."

At the World Economic Forum’s virtual Davos gathering earlier this year, 120 of the world’s largest companies pledged to come up with a set of common metrics and non-financial disclosures to help stakeholders fix the ESG quagmire, with talk from CEOs about seizing an historic opportunity to rebalance the world for the benefit of all.

In updates to the commitment, the WEF wrote: “Since the project began, the ecosystem has seen numerous developments. The European Commission is revising its Non-Financial Reporting Directive. The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) has set out its intention to accelerate the harmonisation of sustainability standards. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has amended its rules to enhance human capital disclosures. The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation has agreed to consult on broadening its mandate to include sustainability issues. The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) has called for the creation of an International Sustainability Standards Board to sit alongside the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) under the auspices of the IFRS Foundation. Meanwhile, the five leading voluntary framework and standard-setters – CDP, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) – have for the first time committed to work towards a joint vision. They presented a paper to the IBC Summer Meeting 2020 and issued a subsequent statement of intent.”

This you might read is precisely the problem of galvanising an institutional response.

Nevertheless, those in the sector argue that financial institutions are best placed to fund the necessary research to cut through to the best market solutions.

“I completely agree that it is always good to do good analysis but there are many things that are very hard to quantify and therefore they suffer,” Swiderski says, offering examples.

Trees

“In the climate solutions area, everybody loves trees, you can

see them, count them, work out how much CO2 they sequester if

they sit there for the next 40 years and everyone can go away and

do their spreadsheets.

"We know that marine environments are critical for the carbon cycle. We know that sea grass absorbs a tremendous amount of CO2, and that marine mammals by the amount they sequester in their bodies when they die are very good carbon absorbers. We know that kelp and mangroves are also a critical part of the carbon cycle, but all these are hard to quantify because they are in the sea. And because we can’t quantify them they are essentially being ignored.”

His explanation mirrors the current data paradox (and obsession) that if you can’t measure it does it even exist?

“Our selection processes are as analytical as they can be but you can’t compare somebody taking a Greek lignite miner to court, which Client Earth has done, forcing the Greek government to agree to phase out coal-fired power generation, to conserving an acre of rainforest."

Swiderski is a passionate advocate with a goal of getting 5,000 people to re-invest in Earth by the end of 2021.

“If we do that, it could represent giving in the area of several millions because obviously it is a function of how wealthy the people are. But it could raise £5 million to £10 million a year. Remember this in an ongoing commitment that people make, it is not just a one-off. The 100 we have so far have said that they are going to do this every year so it is a very high-quality commitment in that sense.”