Fund Management

Get Ready For Growth Surge - The View From Rothschild

Taking the long-term investing view, the private bank is not in the habit of dispensing short-term economic forecasts or opinions, nevertheless the firm's global investment strategist says this is a particularly ripe moment.

In a briefing note yesterday, Rothschild managing director and global investment strategist Kevin Gardiner explained why he is breaking form to discuss what is unfolding for Western economies in short order. "Occasionally, we are confident (or rash) enough to be a little more specific about the future. This is one of those times," he writes.

Here are his comments.

We don’t usually make economic forecasts

This doesn’t mean that we have no views about the future. We

couldn’t offer investment advice without them. But as long-term

investors, those views are very broad. For example,

notwithstanding the evolving wall of worry, we usually expect

economies to grow more often than not (to “muddle through,”

perhaps). We also assume that interest rates and security

valuations will eventually normalise, though our definition of

“normal” is fluid.

Just because something has been the norm in the past doesn’t mean that it will be the norm in the future too. But we feel happier with these views than we would with more quantitative, shorter-term hostages to fortune. They may seem bland, but when set against confidently detailed visions of apocalypse they can be remarkably useful.

That said, occasionally we are confident (or rash) enough to be a little more specific about the future. This is one of those times (though we’re still not offering numbers – even whole ones, never mind decimal points).

A possibility often discussed here is hardening into probability. The stage seems set for western economic growth to surge well in excess of trend for a while – after most of the ground lost to virus suppression has already been retraced. This will look less like rebound and more like momentum.

We feel able to offer this short-term “forecast” after a run of remarkable data, and the confirmation of the looming disbursement of another hefty US fiscal package ($2 trillion is equivalent to roughly a tenth of US GDP).

In addition, the big central banks continue to say that they will not “take away the punchbowl” from any economic party any time soon. Instead they expect to keep official interest rates low and, in the case of the ECB, are even trying to stop bond yields from rising in anticipation of an eventual hike. They are positively encouraging spending to go on a tear.

For the key US economy, those data recently include the highest service-sector ISM survey since it started in 1997, the strongest manufacturing ISM since 1983, and almost a million new non-farm jobs created in March. The surveys in particular are forward-looking, suggesting that a strong first quarter – in which US GDP possibly closed on its pre-crisis level – will be followed by a stronger second.

In the eurozone and UK, the year started more resiliently than had been feared in the face of the tightened COVID restrictions, and forward-looking survey data suggest a vigorous second quarter here too. A combination of (varying) vaccination and adaptation will help – with the contentious EU pandemic recovery fund (and an additional UK fiscal boost) now waiting in the wings.

It is a long time since things pointed so clearly to rapid growth in both the US and Europe. And while we have our misgivings about unnecessarily-generous policy, and are braced for higher inflation, that hangover may be some way down the road. For now there is enough spare capacity, even in the US economy, for surging demand to be met largely by output rather than inflation. Either way, further upward revisions to expected corporate earnings seem likely.

… and a medium-term clarification

This week the IMF became the latest official institution to raise

its estimates of developed world growth in 2021. It is a safe bet

that it will not be the last. In fact, because of the

bureaucratic delays involved in producing such official

projections, it is unlikely even to be the last upward revision

from the fund. The revisions are modest, and the IMF economists

probably didn’t have time to incorporate the last week’s robust

US data in their assessment.

After a fall of 3 per cent in 2020, the fund now sees real global GDP rising by 6 per cent in 2021, compared with a January forecast of 5.5 per cent (5.2 per cent in October). At some stage, probably in the first half of the year (the fund doesn’t offer quarterly details), the level of GDP will regain and pass its pre-crisis levels, confirming the downturn as horribly sharp but short. To its credit the fund always projected a relatively quick rebound, but back in June it was expecting the slump to be larger (at -4.9 per cent).

The room for further upgrades is hinted at by the size of the revisions (the fund’s projected growth rate for 2021 has been anchored at 5-6 per cent throughout), and their prediction that none of the big developed economies will be above pre-crisis projections until 2024, when the US just scrapes it.

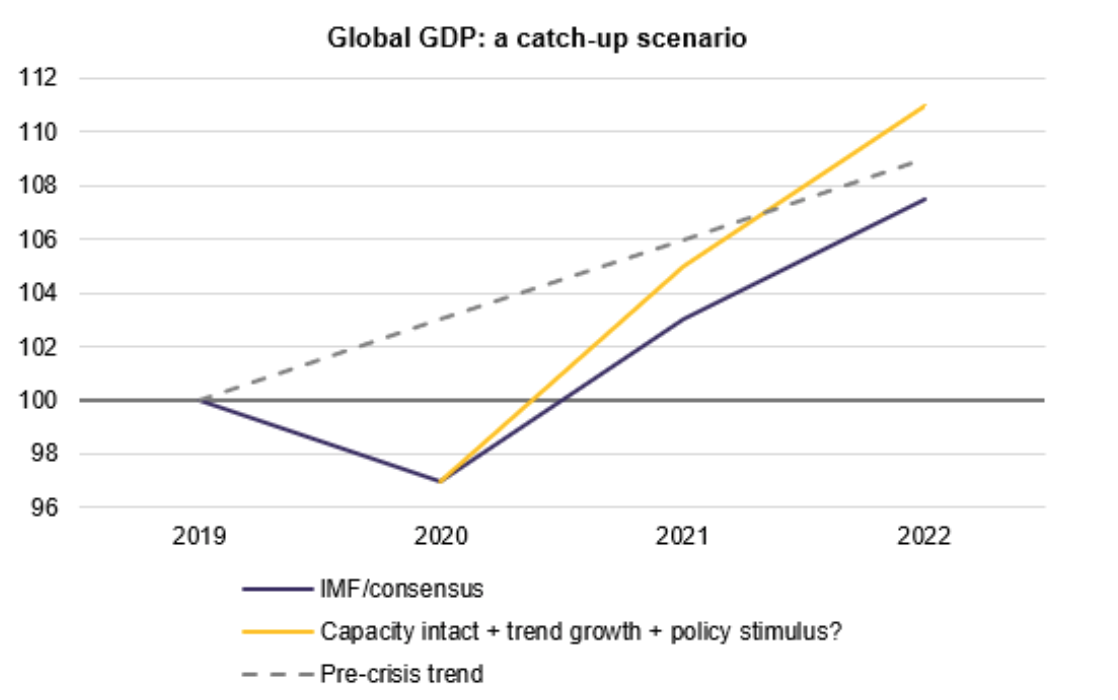

The fund may be overlooking the realistic possibility that global growth doesn’t just catch-up to previous levels, or trendlines, but significantly overshoots for a while, implicitly “making good” some or all of the lost output, the cumulative shortfall between the trendline and the outturn. We have noted here before how the UK’s Office for Budgetary Responsibility may have been similarly unimaginative in their assumptions for the UK.

On this view, the looming surge in growth may turn out to be part of a more prolonged period of unusually rapid expansion. More pessimistic consensus views such as the fund’s understandable focus on the possibility that the downturn has done lasting damage – the possibility that productive assets and workers’ skills are effectively stranded by business failures (and increasingly, educational shortfalls). But what if the loss of capacity is not large – if businesses re-open and adapt, and employment returns, faster than feared?

The chart illustrates a possible catch-up scenario. Trend growth in global productive capacity might be around 3 per cent annum, illustrated by the dotted line in the chart, and may not have been affected much. But on top of this we now have monetary and (especially) fiscal policy that is much more expansionary than it was – and this could take us beyond the pre-crisis trend, for a while at least, as the policy stimulus, which would not otherwise have happened, effectively starts to back-fill the shortfall.

In economist-speak, at this point the “output gap” is shrinking: GDP is above trend, hence the inflation risk noted above. This is not optimistic, but eminently plausible if that closure and re-opening proves relatively frictionless.

Investment conclusion?

Even if we are right with this short-term economic “forecast” and

medium-term open-mindedness, the immediate relevance to

portfolios will still depend on less predictable circumstances.

Guessing correctly that the global economy would shrink

traumatically in 2020 might have led you to shun business

investments – mistakenly, as it turned out.

Equally, the looming surge in growth (and corporate profits) now is no guarantee that stocks will rise throughout.

However, last year turned out well for stocks partly because policy reacted quickly to the economic slump. That support will not be reversed in 2021 at least – as noted, it is even being extended – and circumstances may remain favourable to stocks for a while longer. We prefer them to other assets, particularly bonds; and as our confidence in rebounding profitability rises, more strongly than before.