Wealth Strategies

Ageing Populations Aren't Sure Bet For Healthcare Investors

Too much focus on the ageing theme disregards stronger and even more powerful structural trends from which healthcare investors can benefit, the author of this article argues.

Last week saw a controversial move by the UK government, led

by prime minister Boris Johnson, to push up National Insurance

contributions (for the benefit of non-UK readers, NI is, a form

of payroll tax) to help pay for the National Health Service and

residential care. Regardless of whether this was smart public

finance or politics (we can leave those debates for others), the

affair certainly reminds us of how an ageing population and

rising expectations of medical care are big policy headaches.

Whether the funding comes from taxation or private contributions

in a free market, these forces will be a major part of investment

and business in coming years. There are investment opportunities

to be had. And wealth management clients need to be on their

game.

To discuss these issues is Kay Eichhorn-Schott, portfolio manager

at

Berenberg Wealth and Asset Management. He points out

that the trend of an ageing population is not a sure route to

improved healthcare investment outcomes. This is also a global

concern, and important in countries such as the US, which has

large private sectors.

The editors are pleased to share these views on this very

important topic, and invite responses. The usual disclaimers

apply to views of outside contributors. Jump into the

conversation. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com

Many members of the investment industry have long argued that the

ageing of Western societies is providing a strong secular

tailwind for healthcare companies. This is an important insight

but the ageing trend alone is not enough to ensure success for

investors in healthcare. Many healthcare companies face an uphill

battle to turn a profit, while others come with binary risk

profiles; one poorly performing drug and they are in the red.

Demographics won’t necessarily save them.

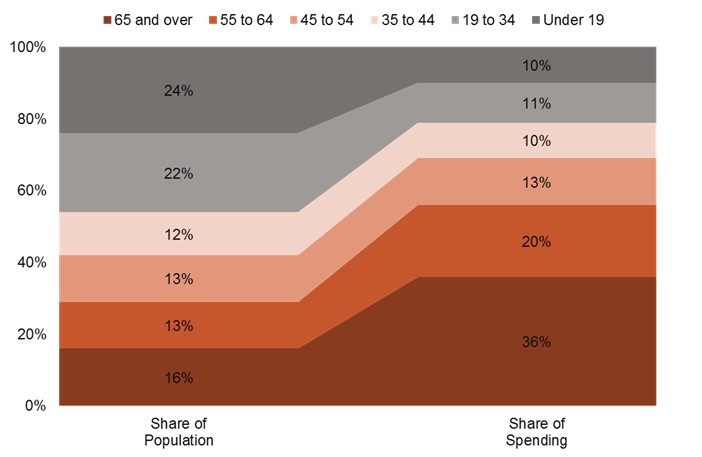

However, a glance at the statistics might suggest that those

betting everything on ageing have it right. According to the

United Nations, in 2020, 9 per cent of the world’s population was

65 and older with the percentage rising to 16 per cent by 2025

and 23 per cent by 2100. We all realise that the elderly consume

more healthcare dollars than the young. A statistic from the

Kaiser Family Foundation illustrates this well: people over 65

represent only 16 per cent of the US population but account for

36 per cent of healthcare spending (see Figure 1). As societies

age, so, the argument goes, healthcare spending is set to balloon

and healthcare investors will benefit.

There is a big problem with this argument. It rests on the

assumption that expenditure per capita will stay constant. Yet it

is unwise to rely on this assumption.

Figure 1: People aged 55+ account for more than 50 per cent of

healthcare spending in the US

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

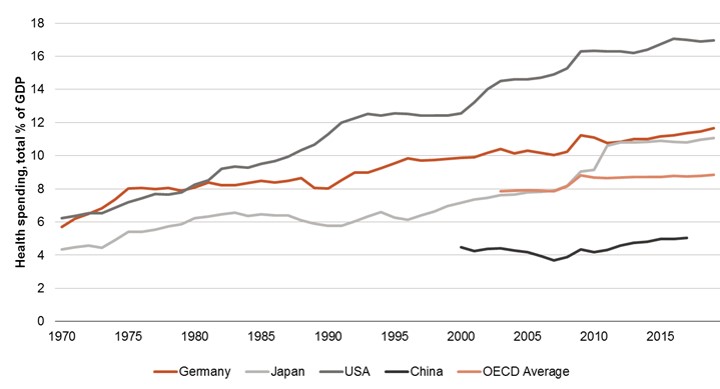

When considering today’s global healthcare expenditure (see Figure 2), a continuation of higher and higher health spending simply does not seem sustainable. In the world’s largest healthcare market, the US, already 17 per cent of GDP is spent on healthcare, a number that the country cannot afford to increase much further. In fact, we expect that the US will need to find ways of reducing healthcare spending per capita. This could be through price erosion or simply by finding more efficient ways of delivering the same quality of care. Betting on a continuation of higher healthcare spending driven by ageing doesn’t take this into account. Ageing alone will not drive abnormal growth for many companies.

Figure 2: Healthcare spending is on the rise

Source: OECD, 1970 - 2019

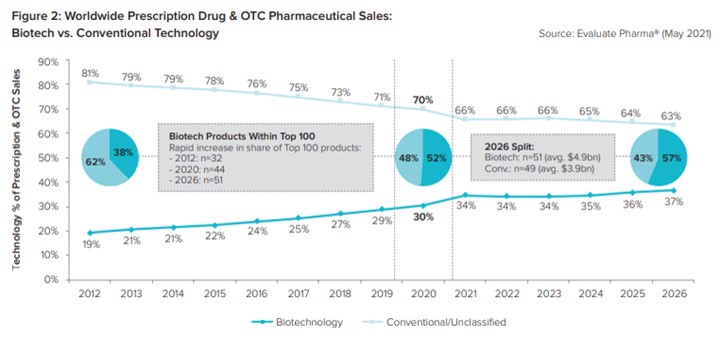

Rather than investing broadly in the ageing trend investors need

to find companies benefiting from more specific and stronger

tailwinds. One of these trends is the rise of biologic drugs. In

contrast to traditional drugs, biologics consist of larger and

more complex molecules, which also require different production

processes. In recent years, we have already seen a strong shift

towards these new drugs as they are more targeted and for that

reason also more effective. Monoclonal antibodies are the largest

group of biologic drugs; however, there are also new biologic

drugs on the rise, such as antibody drug conjugates (ADCs),

bi-specific antibodies or cell and gene therapies.

Interestingly, much of the innovation in biologic drugs happens

at smaller companies like biotechs rather than big pharmaceutical

companies, as illustrated in Figure 3. The advent of COVID-19

vaccines based on the messenger RNA (mRNA) technology serves as a

great example of this phenomenon. It was not the large

pharmaceutical companies that came up with these life-saving

treatments, but previously small and relatively unknown biotech

companies like BioNTech and Moderna.

Figure 3: Biologic drugs are on the rise

Source: Evaluate Pharma

Investing in pharmaceutical innovators can be tricky. We have

never been huge fans of large pharmaceutical companies. While

their revenues are mostly well diversified across many products,

they typically face an uphill battle: new products need to

compensate (and sometimes overcompensate) for the weakness of

older products due to stronger competition or patent expiry. This

often leads to relatively low growth for these large

pharmaceutical companies.

Investing in small biotechs presents a completely different

challenge. Often, such companies have limited revenues today and

are loss-making. What’s more, their success may depend on one or

a few pipeline products, so the range of outcomes from complete

failure to huge success is wide. If investors do not have strong

convictions in the pipeline, they should stay away. To still

benefit from the overall rise in new drugs from smaller players,

without exposure to this very binary risk, we prefer investing in

companies supplying the drug developers.

Figuratively speaking, in the biologics gold rush, we prefer

investing in the shovels rather than the gold miners. One such

shovel is Lonza, a contract development and manufacturing

organisation (CDMOs).

The company is a specialised manufacturer of pharmaceutical

ingredients and end-products for pharmaceutical and biotech

customers. Lonza benefits from the strong demand for biologic

drugs and an increased appetite for outsourcing manufacturing.

Pharmaceuticals are increasingly relying on CDMOs to manage their

manufacturing capacity more flexibly. In addition, as drugs

become increasingly complicated, CDMOs can offer expertise that

their customers do not have.

CDMOs such as Lonza typically have a large number of customers

and are not dependent on any one drug’s failure or success. For

example, Lonza has formed a multi-year partnership with Moderna

that extends beyond COVID-19 vaccines and entails developing and

manufacturing vaccines against flu. Historically, the vaccine

market has been an oligopoly between many large incumbents that

largely produce their vaccines in-house. With the rise of mRNA

vaccines, newer players will probably enter the market and rely

more strongly on CDMOs such as Lonza for production.

The outsourcing trend in the pharmaceutical industry goes even

further: not only is manufacturing increasingly undertaken

externally but the innovation and drug discovery process is

outsourced too. The reasoning is straightforward. Due to higher

regulatory standards and treatment targets becoming more complex

the development costs for drugs have risen considerably. At the

same time, the potential payoff has shrunk as drugs become

narrower in their application and more targeted in their patient

population. Deloitte estimates that the average development cost

per pipeline project increased by 84 per cent to $2.4 billion

between 2013 and 2020. Yet, during the same time, average peak

sales per asset decreased by around 19 per cent to 421 million.

Unsurprisingly, returns on R&D expenditure have seen a steady

decline.*

To fight this, pharma and biotech companies are increasingly

partnering with clinical research organisations (CROs), such as

the German company Evotec, to identify drug targets, develop

molecules and also manufacture the final product. Evotec has

developed a model in which the company also invests in a number

of pipeline projects where it partners with pharmaceutical

companies, such as Bayer or Bristol-Myers Squibb for further

development. The model has been successful to date and the entire

industry is experiencing strong demand for these collaborations

between large pharma partners and small innovators.

In conclusion, investing based on the ageing theme alone is risky

because healthcare spending per capita, especially in the markets

like the US, could easily start to decline. Too much focus on the

ageing theme also disregards stronger and even more powerful

structural trends from which healthcare investors can benefit.

The rise of biologic drugs and the increasing use of outsourcing

are two examples. The healthcare investment universe does present

long-term oriented investors with a large opportunity set of

innovative companies with strong growth prospects and sustainable

competitive advantages but they have to know where to look.

Reference

*Deloitte 2021, Seeds of Change, Measuring the return from the Pharmaceutical Innovation